Art, like the body, breathes. It pulses with the lifeblood of centuries, capturing the gaze we turn inward, the reverence we reserve for our own skin, and the discomfort we sometimes feel in it. To trace the history of body image in art is to witness a visual dialogue between the soul and the flesh—a conversation that ebbs and flows with each era’s desires, anxieties, and ideals.

In ancient Greece, the body was a temple, both in metaphor and in marble. The male form, carved by artists like Polykleitos, became a study in geometry, symmetry, and a declaration of perfection. But within this pursuit, there’s the tension of unattainable perfection, a dream shimmering just out of reach. The bodies that adorned temples were as much about the divine as they were about human fragility. The Greeks, though obsessed with beauty, couldn’t escape the weight of being mortal, a truth that lingers beneath the chiseled bodies and heroic poses.

By the Renaissance, the human form had bloomed with the vibrancy of rediscovery. Michelangelo’s David stands not just as a figure of strength but of vulnerability, his poised stance a quiet rebellion against the confines of idealism. There’s tension in his marble veins, the readiness to strike but the stillness of contemplation. Additionally, emerging from the sea foam in Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, Venus is both ethereal and elusive. Her beauty is worshipped, yet her body, impossibly perfect, is as distant as the gods themselves.

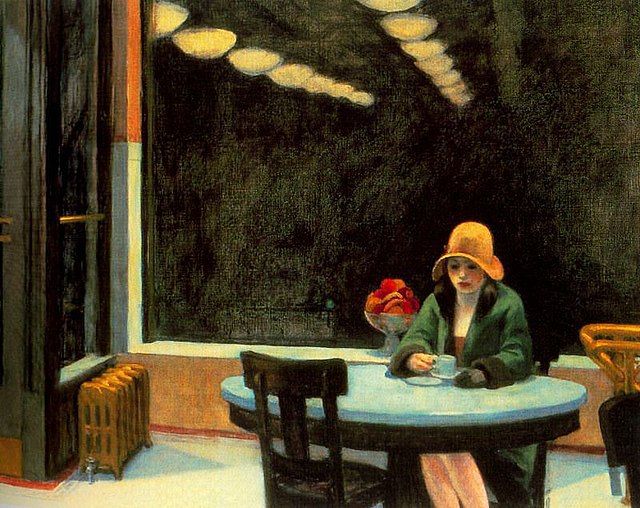

Then, around the 19th century, body image became less about ideals and more about the realities that live beneath. With his ballerinas, Degas offers us bodies in motion, weary and worn, bent by the unglamorous labor of dance. These aren’t the poised figures of a Grecian frieze but raw human bodies. They stretched, slumped, and ached. With exaggerated features and crooked smiles, Toulouse-Lautrec’s cabaret performers also peel back the romantic gild of beauty, daring spectators to see bodies not as ideals but as deeply, unapologetically human.

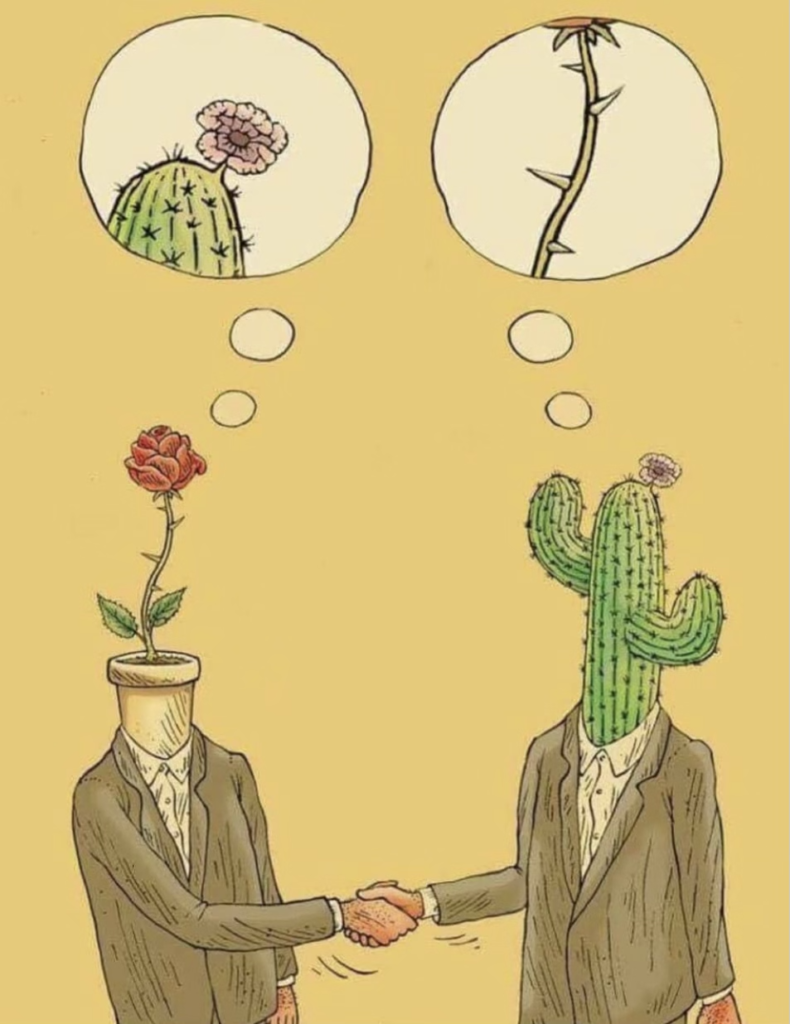

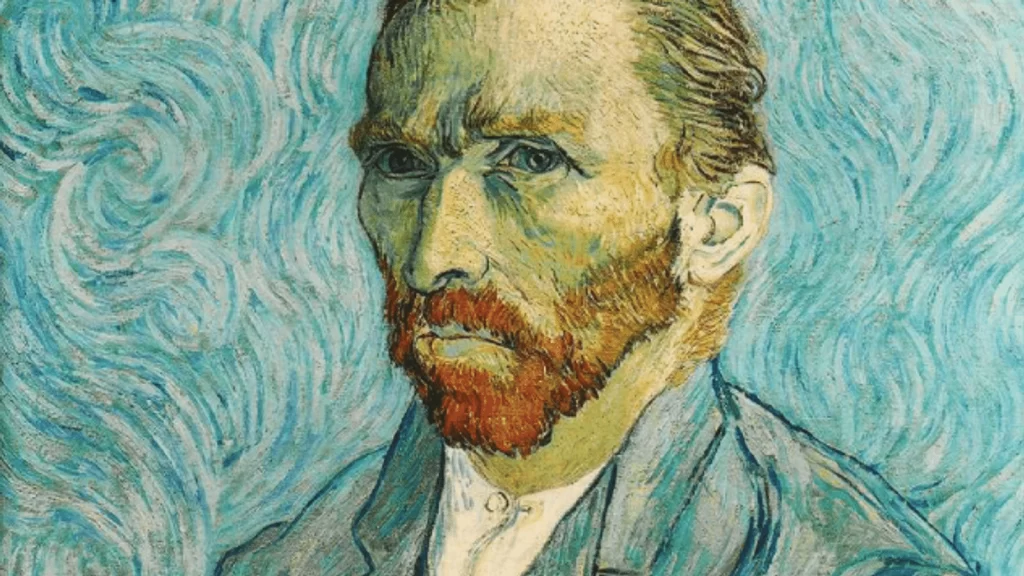

There’s also the 20th century, which includes notable figures like Picasso, who took the body and broke it, piece by piece, fragmenting our vision, as if to remind us that nobody can be seen all at once. A person holds layers, which may be discovered with further connection. Picasso’s figures no longer conform to the gaze of perfection but defy it, existing in angles and planes, reassembled by the viewer’s eye. Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits go even further, leaving viewers breathless. Her body a landscape of pain, her spine a column of brokenness, and her flesh a pinboard of thorns, yet her eyes, unflinching, hold the power to reclaim her being as her own.

Today, body image in art has blossomed into a tapestry of reclamation and diversity. Kehinde Wiley and Jenny Saville elevate the body in all its forms, rejecting, resisting, and rewriting centuries of art history that sought to confine the body to a singular mold. The body is imperfect, vulnerable, strong, and the most eternal subject. Through every sculpture, every brushstroke, and every line, the same truth prevails: the body, in all its forms, is art itself.